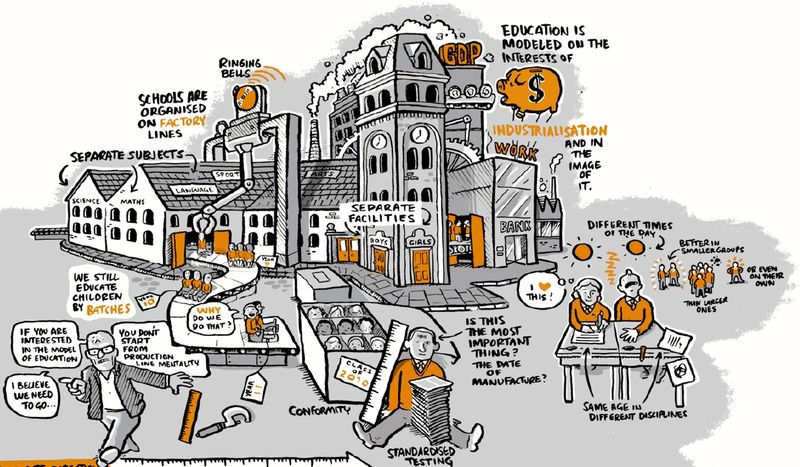

Trust has become a hot topic of late. With increasing polarization in political parties and decreasing trust in government, many are becoming more concerned about the corrosive effect of this loss of trust on our capacity to effectively govern. This loss of governance capacity has at least 2 potential effects: large societies may become unstable and we won’t be able to respond to global problems like climate change. It is fairly straightforward to establish relationships between higher levels of trust and better economic performance and less income equality and less trust. But what is trust, anyway? If it is so critical and we have to manage it, we need to know what it is.

In the statistical relationships above, ‘trust’ is measured by simply asking people whether they trust their neighbors or not. Our World in Data says trust is a critical element of social capital. But there is no agreement on what social capital is either. Both social capital and its derivative, trust, are often characterized by what they do rather than what they are. But if we are to build trust and understand what erodes it, we need to know what it is, not what it does.

Social capital has been defined by many well-known scholars in various ways. Some seem to emphasize its private value, e.g. Pierre Bourdieu defines it as a sum of resources that flow from the possession of a social network and Glenn Loury defines it as social relationships that promote or assist acquisition of valuable skills and traits. Robert Putnam, on the other hand, suggests it is a public good, e.g. as trust, norms, and networks that facilitate coordinated actions. James Coleman defines social capital as some aspect of social structure that facilitates certain kinds of interactions leaving its public or private nature unclear. If asked, I would guess that all these scholars would agree that social capital provides both public and private value streams as many types of infrastructures do. But we are still left with the question of exactly what social capital is as all these definitions are about what it does.

Perhaps Paul Romer put it best in his definition of human capital as the neural networks in our brains and our bodies that encode knowledge. Some of this information is about what others in our social networks will think and do in certain situations. Social capital may thus be defined as this shared information which has both a private and public character. This information is costly to obtain and we can take shortcuts and make guesses about what others think and do based on aggregated information from the media and in-group out-group perceptions reinforcing trust of in-group members and erode trust out-group members. The fact that trust is linked to reputation and branding creates opportunities for individuals to free-ride on shared trust and use it to manipulate others that are ‘too trusting’ leading to potentially very negative consequences.

The many problems that face societies today do not discriminate between various social groups. These problems require trust across all groups, i.e. trust as public good. However, our attention is limited which, in turn, limits our capacity to maintain social capital. If we are to build trust, our investments must focus on areas that emphasize its role as a public good. We need infrastructure that makes it easier to connect with others face-to-face and makes public trust more difficult to exploit. Building trust is expensive, but it may be our most valuable shared asset.