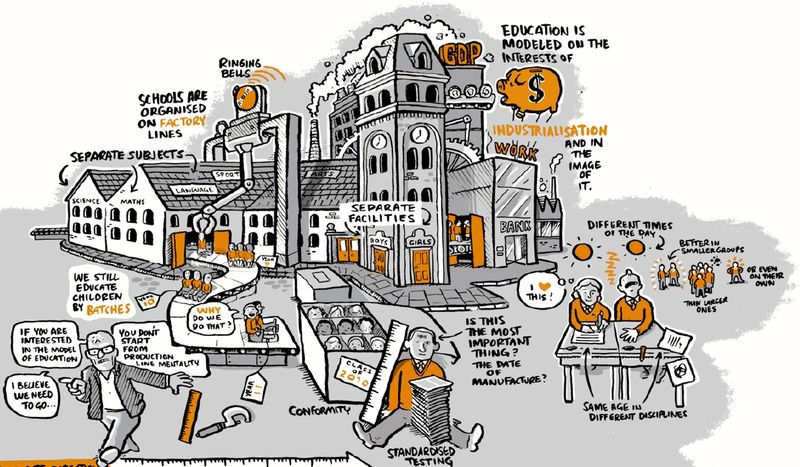

A popular saying is “it takes a village to raise a child”. While certainly true, raising a child this way is difficult to scale up. As a result, in modern times, we have created a formal educational system that serves an industrial economic model of a standard 9-to-5 work day for adults that does not necessarily provide children with the best learning experience. Is learning best concentrated in a 9-to-5 work day schedule? Further, the current model of K-12 education in the US was designed, in part, to meet specific needs of the industrial revolution such as basic, standardized, transferable skills. The mode of delivery is also based on ideas from the industrial revolution where kids are educated in age batches and forced to fit a set of standards based on thinking from a past age. Are there really ‘standard’ skills and batches of ‘standard kids’ to be transformed into adult workers? How might the schedule and content of formal education fit with the realities of modern work lives where traditional 9–to-5 jobs are becoming less common (e.g. the emergence of flexible hours, odd shifts, etc.) and the skills and knowledge required for career success are rapidly changing?

The situation we find ourselves in where the work lives of adults and the learning lives of children are coupled by industrial logic limits our capacity to cope with change. Worse yet, this industrial logic is poorly equipped to address the diversity of personalities and learning styles in human populations. In his recent book The Orchid and the Dandelion, pediatrician Thomas Boyce details how subtle differences in human psychology impact human development and outcomes. Orchid children are exquisitely sensitive to context. As the name suggests, in the right context, they can achieve brilliance. In the wrong context, they cannot thrive. Dandelions, on the other hand, are children who can thrive anywhere but may not be able to reach the heights of an orchid. Dr. Boyce argues that our human development infrastructure must be reimagined to take these differences into account. Cultivating human diversity requires diverse learning modalities that allow for self-direction and agency. The industrial logic of routinization and standardization is not well-suited to address these needs.

The challenge here is related to our past investment choices in infrastructure and the cost of standardization. One such cost is the need for coordination across time and various activities (i.e. adults working and children learning) that the Covid-19 pandemic brought into sharp relief: an important function of formal education is simply to provide day care to allow adults to work. The pandemic highlighted a conflict between human development (learning) needs of future generations and day care needs of the present generation. What could a post-industrial model of human development and day care infrastructure look like?

First, we need to be clear about the trade-off in accommodating the welfare of children and facilitating the needs of the current economic system. Second, we need to decouple the institutions that govern adult working lives and those that govern the developmental needs of children and recognize that this will come at a cost. Customized attention for individual learners requires highly skilled and expensive human input. This will require that we increase our investment in learning infrastructure systems to facilitate the needs of children which, in turn, could have long term benefits in human development and mental health. Is society willing to make these trade-offs?