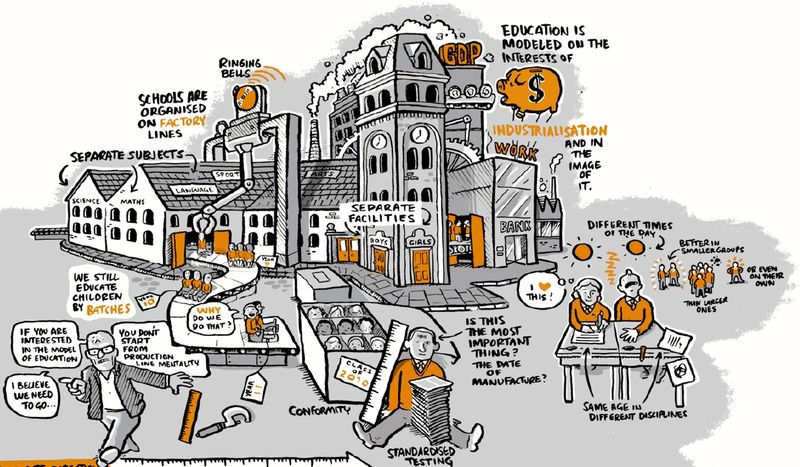

For academic careers it is essential to publish your work in reputable peer-reviewed journals. Publish or perish – the pressure to publish – leads to an increased level of research output (about 2 million articles a year), but it is less clear whether it has increased the quality of knowledge production at the same rate. There is a limited amount of time a scholar can spend on their scholarly activities, and one has to balance investing time in producing new output and evaluating the outputs of others, an essential part of knowledge production. From my experience as a reviewer, editor, conference organizer, and author, I sense that many scholars like to publish and speak, but not so much to read and listen to the work of others. This is no surprise since the incentive in academia is to produce a large volume of output, not high quality output. This problem is exacerbated by predatory journals and conferences who exploit the pressure to publish, often without any review process.

When, in the seventeenth century, science experienced a revolution, scientists exchanged their findings in letters to colleagues which eventually led to early journals like the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. As such, academic journals scaled up the spread of information within correspondence networks between scholars. Originally the academic journal was a formalization of investments in social infrastructure, the spread of information from societies and scholarly networks. Nowadays, journals are open to a global community beyond members of an academic society, and those publishing in journals supported by an academic society are often not related to the academic society. Scaling up the academic publishing process makes it less personal and less social.

There have been unverified estimates that about half of the published articles are not read other than by authors and reviewers. Whether this is true or not, scholars may probably agree that their work is less read than it should be. The overprovision of research output might be the consequences of incentives to value output production, and not the quality of the output. And since much of the work is not read anyway, everybody might be happy: the authors, the sponsors, and the publisher. But as a society we may waste resources to produce outcomes that are not used. Moreover due to the “pollution” of so much research output, the published diamonds might be hard to discover.

Could we incentivize scholars to invest more time in evaluation (a contribution to the public good) versus production (also a contribution to the public good, but with a private recognition and reward)? How might we stimulate reviewers to provide more constructive substantial feedback, and authors to archive detailed descriptions of the methods used so that others can build on the research produced, do a thorough review of existing literature, and write papers with meaningful and interesting research questions?

As an editor-in-chief, it is difficult to recruit reviewers who provide thoughtful reviews. It is not not unusual to invite 20 relevant scholars to get 2 reviews within a six month period. This is disappointing for all parties involved. As an editor-in-chief I find it flabbergasting that authors of recent papers published in the journal often refuse to review a manuscript (because they are too busy!) and thus freeride on the evaluation efforts of others.

One suggestion would be to incentivize the contribution to high quality review by registering one’s review activities by services like Publons and those journals involved could give priority to handling manuscripts of those who are in good standing of review activities versus publishing. This should not mean that quality standards are adjusted, but those who send in a lot of manuscripts for review should also invest their fair share in quality review in order to get their manuscripts sent out for review.

Such a centralized accounting system of publishing and reviewing may sound Orwellian, but largely exists already. Instead of focusing on publishing more, we should use this information to find ways to publish better.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/02/bf02c9f2-73b8-4fb0-b6e6-bd81d34822f7/2099848735_d5241ea070_o.jpg)